All this is happening above our heads

Our Atmosphere and the Greenhouse Effect. 1/2

By Michel Gravereau

Not a day goes by without hearing in the media that this or that event is due to "global warming." It's a convenient scapegoat.

Undeniably, the warning lights are flashing red, and despite the good decisions made by some, bad habits persist. The latest report indicates a slowdown in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions for France in 2025 and a significant increase in emissions for the United States. France accounts for only 1 percent of global emissions.

I would like to remind you that scientists' concern about global warming is not new, since as early as 1873, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) was already holding meetings on the subject. This would lead much later to the first Earth Summit, held in Rio in 1992.

At the time, Mr. Diesel hadn't invented his engine, and airplanes weren't crisscrossing our atmosphere. Let's try to get a clearer picture of our Earth's atmosphere and what we call greenhouse gases.

How far does the Earth's atmosphere extend?

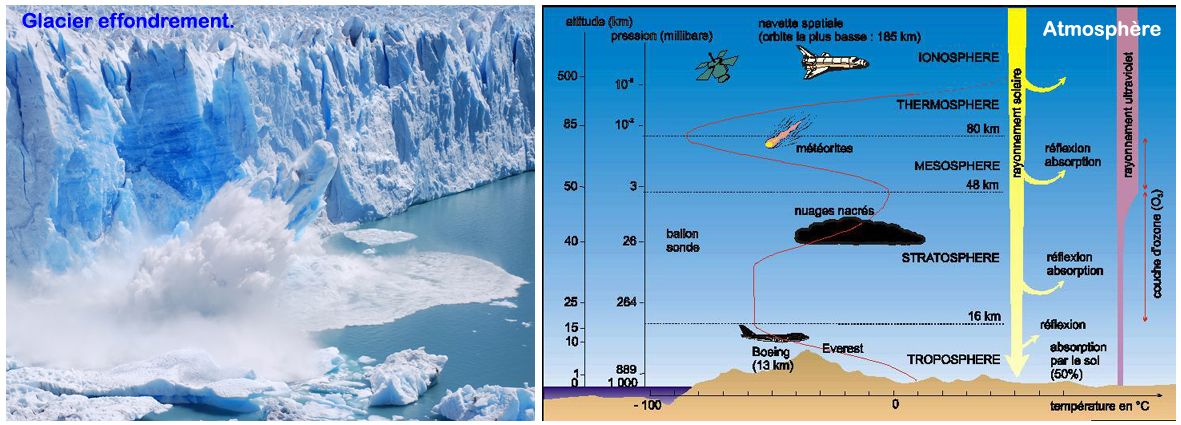

99.999% of the air is found below 80 km altitude, which is why we often consider that the Earth's atmosphere ends at this level.

However, air particles can still be found at an altitude of 750 km. Thus, there is no clearly defined physical boundary separating the atmosphere from empty space, just as there is no precise time of day marking the transition from day to night.

At our latitudes, we know that it is dark at midnight and light at noon. But at what exact time does the transition from day to night occur? Not so easy to say… The difficulty is the same when trying to determine where the boundary lies between the Earth's atmosphere and interplanetary space.

Indeed, while the air gradually thins out as one ascends in the atmosphere, there is no precise altitude at which one abruptly transitions from air to a vacuum, unlike what is observed when moving from water to air.

From a physics perspective, it is estimated that above 800 km altitude, the average distance between air molecules is such that we can no longer speak of an atmosphere, for the same reason that we cannot call a group of people separated from each other by several hundred kilometers and not communicating with each other a "society."

However, air particles can still be found at an altitude of 750 km. Thus, there is no clearly defined physical boundary separating the atmosphere from empty space, just as there is no precise time of day marking the transition from day to night.

At our latitudes, we know that it is dark at midnight and light at noon. But at what exact time does the transition from day to night occur? Not so easy to say… The difficulty is the same when trying to determine where the boundary lies between the Earth's atmosphere and interplanetary space.

Indeed, while the air gradually thins out as one ascends in the atmosphere, there is no precise altitude at which one abruptly transitions from air to a vacuum, unlike what is observed when moving from water to air.

From a physics perspective, it is estimated that above 800 km altitude, the average distance between air molecules is such that we can no longer speak of an atmosphere, for the same reason that we cannot call a group of people separated from each other by several hundred kilometers and not communicating with each other a "society."

As a reminder, a molecule is an assembly of atoms. In our atmosphere, these are primarily nitrogen (80%) and oxygen (19%) molecules.

But for space engineers, the 110 km mark is a critical limit, because it is at this altitude that objects hurtling towards our planet (meteorites, spacecraft, etc.) begin to burn up due to the friction exerted by air molecules.

According to international regulations, outer space is considered to begin at an altitude of 80 km. This is where 99.999% of air molecules are confined.

It's worth noting that 0.999% makes all the difference, since 99% of the air is found below 31 km altitude. Most of the weather phenomena that affect our atmosphere occur in a layer called the "troposphere," whose thickness varies from 8 km at the poles to 18 km at the equator.

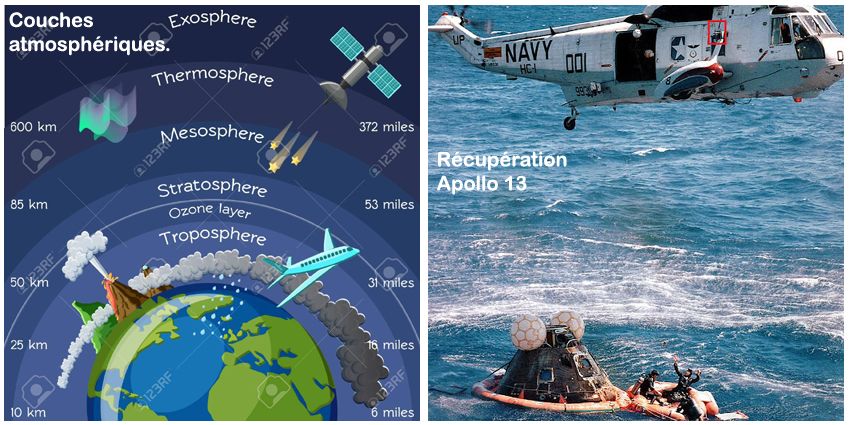

For astronauts, the boundary of the dense layers of the atmosphere (around 110 km altitude) is a very real reality. Because if its angle of attack is too wide, a spacecraft returning to Earth risks bouncing off its layers, like a pebble skipping across water, and drifting off again into space.

The problem arose dramatically in 1970, during the return of the Apollo 13 mission, whose navigation systems were all out of order. Navigating "by sight," at a speed of 40,000 km/h, the capsule was able to orient itself correctly, avoiding disaster.

But for space engineers, the 110 km mark is a critical limit, because it is at this altitude that objects hurtling towards our planet (meteorites, spacecraft, etc.) begin to burn up due to the friction exerted by air molecules.

According to international regulations, outer space is considered to begin at an altitude of 80 km. This is where 99.999% of air molecules are confined.

It's worth noting that 0.999% makes all the difference, since 99% of the air is found below 31 km altitude. Most of the weather phenomena that affect our atmosphere occur in a layer called the "troposphere," whose thickness varies from 8 km at the poles to 18 km at the equator.

For astronauts, the boundary of the dense layers of the atmosphere (around 110 km altitude) is a very real reality. Because if its angle of attack is too wide, a spacecraft returning to Earth risks bouncing off its layers, like a pebble skipping across water, and drifting off again into space.

The problem arose dramatically in 1970, during the return of the Apollo 13 mission, whose navigation systems were all out of order. Navigating "by sight," at a speed of 40,000 km/h, the capsule was able to orient itself correctly, avoiding disaster.

Greenhouse effect.

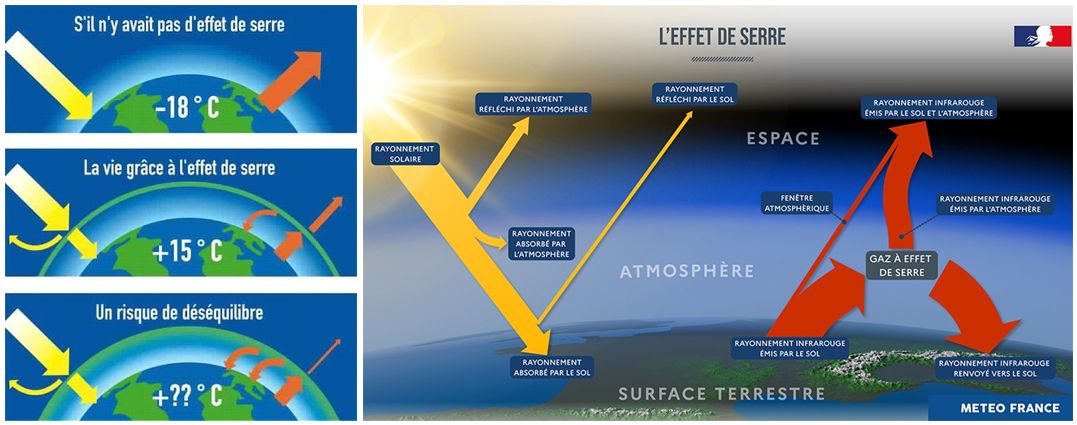

The atmosphere traps the heat emitted by the Earth, which is itself heated by the Sun. It's like a greenhouse, where the glass allows sunlight to heat the interior but prevents that heat from escaping.

This natural greenhouse effect is a blessing. Without it, the Earth's surface temperature would be -22°C. But human activities are amplifying this effect, risking overheating the planet. For several years now, the term "greenhouse effect" has been directly associated with the fear of devastating global warming.

But this overlooks the fact that the greenhouse effect is one of the mechanisms that has allowed the Earth's atmosphere to maintain a global temperature of 15°C, making our planet suitable for supporting life.

This natural greenhouse effect is a blessing. Without it, the Earth's surface temperature would be -22°C. But human activities are amplifying this effect, risking overheating the planet. For several years now, the term "greenhouse effect" has been directly associated with the fear of devastating global warming.

But this overlooks the fact that the greenhouse effect is one of the mechanisms that has allowed the Earth's atmosphere to maintain a global temperature of 15°C, making our planet suitable for supporting life.

To be continued...